Assessment of Student Writing in the Age of AI

When Organization, Grammar, and Punctuation are Correct, What's Left?

(I have recorded this post for your convenience.)

One of the most significant lessons my colleague, Eugenia Novokshanova, and I have learned from teaching with generative AI over the past year is that we need to have a new vision regarding assessment of student work. We can assume our students' papers are organized correctly, and that grammar and punctuation is correct, so those items no longer appear on our student rubrics. Instead, we are concerned with the following:

Are the facts correct?

Did students follow our assignments EXACTLY?

Do we see evidence of creative integrity, voice, and critical thinking?

Are the Parenthetical Citations and the Works Cited done correctly?

Did they acknowledge their use of AI?

In our classes, students OWN their work. They cannot skate by with inaccurate facts and faulty reasoning with the excuse that they were spending time struggling with grammar and punctuation, as that part of the writing is taken care of with generative AI. We no longer teach at the word, sentence, or paragraph level, except when we have specifically created an assignment to work “against AI.”

Our new concern is with our students’ thought process, their use of CORRECT facts (i.e., did they read the assigned reading carefully and respond to it with intelligence and critical thought?), and their careful assembly of correctly cited evidence.

In the era of AI, we expect students to spend time thinking about what they want to say and how they want to say it. AI should be able to make sure it is error-free, but they must carefully control what it says about the topic, and ensure that what it says is correct. Students should be held responsible for the correctness of the information they submit. We remind them to never use AI to write about anything they do not know. AI will hallucinate, and students must understand the material well enough to catch a factual hallucination, as there is no excuse for inaccurate facts.

Transparency is essential to this process. Students should get into the habit of recognizing their use of AI and critically evaluating their AI use. They must understand how they use AI, and how they own the AI that they use. Their ideas, voice, and personality must not be hijacked. In understanding how they use AI, they should also understand how it varies depending on the assignment and their message. They may use any of the following approaches:

"Write First Approach" - This involves writing the draft first, and then using a “writing tutor” prompt or grammar and spell check to perfect the paper.

"AI First Approach" - This involves using AI to brainstorm, outline, narrow, test claims, and invite creative approaches to writing.

"Selective AI Approach" - This may start with an AI outline that is then heavily edited or rearranged; or they may begin with writing their own claims or theses and using AI to further narrow them; or they may write some and ask AI for help in figuring out how to reorganize, revise, or expand sections of their work.

When we ask our students to carefully consider and reflect on how they use AI, they become better and more informed writers. They must be taught to consciously consider involving technology in their creative process, and they must build understanding by making a habit of being transparent with themselves and others about how and why they use AI. In our class, this takes the form of an “AI Use Disclaimer.” Every time they turn in an assignment, they are expected to tell us:

If they used AI,

What AI tool(s) they used,

How they used that tool, and

Why they used that tool.

In order to promote the honesty of our students in our courses, we offer a “sanctuary policy.” If they are honest with us, we will not fail them—even if they have overused or inappropriately used AI. In most cases, our students have used AI appropriately because we teach them how to do that. However, in the case of inappropriate or unethical use of AI that is accompanied by an AI Use Disclaimer, we will assume the student was unsure about how to use AI appropriately, and instead of a failing grade, we will offer advice on how to use AI correctly, and allow them to revise and resubmit their essay.

Even though the idea of AI transparency to others may lose importance in the future when everyone is using AI for everything, we still think it is important that our students can be transparent with themselves. Good habits should be established early and reinforced often.

Formative vs. Summative Assessment

Finally, we are teaching our courses as a series of projects that must be completed for a certain percentage of the course grade. As part of each project, we use formative assessment, giving credit along the way for each assignment rather than offering a “winner-take-all” summative assessment at the end of the module. According to Paul Black and Dylan William in their paper, “Developing the Theory of Formative Assessment (2009),” formative assessment is paramount to improving learning and outcomes in education, “A formative interaction is one in which an interactive situation influences cognition, i.e., it is an interaction between external stimulus and feedback, and internal production by the individual learner” (Black and Wiliam). In other words, we assign a lesson that our students complete. Then, we give them feedback that not only helps them to understand the assignment they have completed but also prepares them for the requirements of the next assignment. This requires a substantial commitment from the instructor, it is true. We need to respond to our students' small, formative assignments on a regular basis and give them significant and specific feedback so that they can continue toward the goals of the course. Our formative assessment process takes the form of small, frequent assignments with small percentages for the project grade.

Timeline for Rhetorical Analysis Project (35% of Course Grade)

Week 5 Assignment: Academic Summary--10%

Week 5 Discussion: Rhetorical Situation Analysis Draft--10%

Week 6 Assignment: Modal Mind Map--10%

Week 6 Discussion: Modes and Rhetoric--10%

Week 7 Discussion: Modal Analysis Draft--10%

Week 8 Assignment: Rhetorical Analysis Essay (Final Draft)--20%

Week 9 Discussion: Recomposed Essay--20%

Week 9 Discussion: Project Reflection--10%

Sometimes we get a student who has not attended classes regularly, and who has not kept up with the work. Often, those students will come to us asking if they can “just make up the paper.” Our answer must be, “I’m sorry, but the paper is only 20% of the grade.” The truth is that everything in our class is scaffolded upon every other thing in our class. A student can’t complete one assignment without doing all the work leading up to that assignment.

Our Rubrics

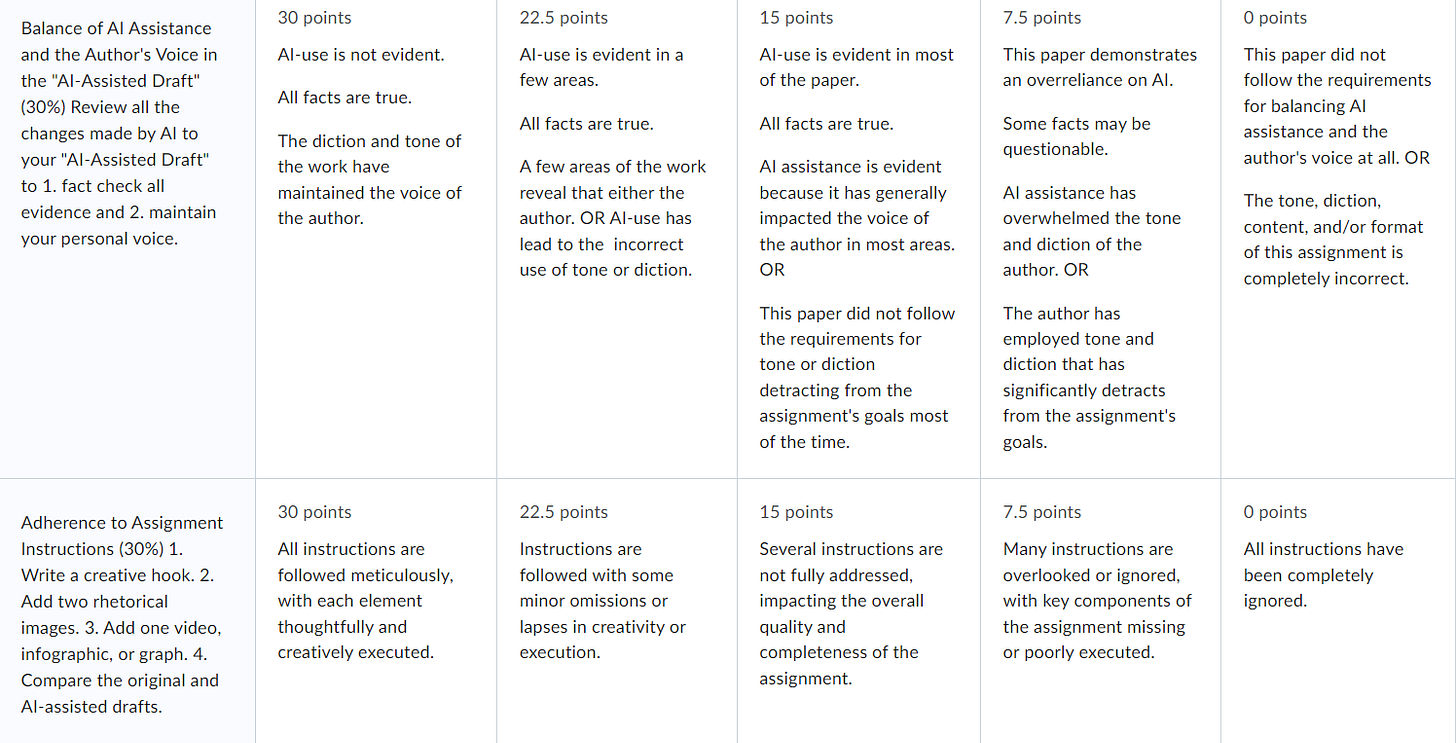

Because of the high demand for assessment in our courses, we depend on rubrics to grade our assignments. Together, we have worked very hard to make our rubrics conform to the things we believe are important to the purpose and scope of our courses. If there is one thing that has helped clarify our grading of student assignments and simplified our understanding of a well-written AI-infused paper, it is our rubrics, and they have significantly changed our teaching practices. Before AI, our rubrics were mostly traditional – focusing on grammar, punctuation, organization, etc. However, we soon recognized that those were not the basis of our grading any longer. Now, a rubric might look more like this:

The significance of a rubric like this cannot be overstated. In a world where our students can easily access AI, and where they are somewhat proficient at using the tool, we have decided that it is not the use of AI that is the problem in student writing. In fact, we want our students to use AI, but we also want them to use it correctly. AI use isn’t something we can prove, so we have given up trying to do that. We have stopped trying to guess whether our students have used AI. Instead, we have decided that whether they have used AI or not, they must display significant control over their own voice and their own creative decisions.

When we see a paper that is overly wordy, that uses an artificial tone that our students would never normally use, or a paper that seems to lack a spark of creative control, it doesn’t matter whether they used AI or not—it’s a bad paper. Likewise, if we have carefully created an assignment and our students don’t follow the requirements, it doesn’t matter whether they used AI or not because we mark them down for failing to meet our requirements. It doesn’t matter whether they failed because they used too much AI, or whether they just missed the mark.

Works Cited

Black, Paul, and Dylan Wiliam. “Developing the Theory of Formative Assessment.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, vol. 21, no. 1, Feb. 2009, pp. 5–31. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5.

Well the time has come that I've made the shift to "let's teach them how to use AI." Thank you for being a guide on this journey, even when I was not keen on joining it. Next week I present to my smaller team how to discuss AI with students and your work is going to be invaluable (and attributed properly!).

This is marvellous! So very grateful to you for sharing.

This is such a great way to build an explicit understanding of the human. I’ve been wondering whether spelling mistakes and other idiosyncrasies might become markers of authenticity. But then I wonder whether someone will make a GPT called ‘authentic voice’ or similar! 🤣 No wonder I don’t sleep!