What is "Cheating with AI" Anyways?

It all depends upon how we frame critical thinking in the Age of AI

Last semester,

and I got into a very interesting conversation about what constitutes “critical thinking.” We were looking for a specific term, a way to discuss the issue that was both comprehensive and practical:“Critical Thinking” is such a wishy-washy term. I mean, no one ever has a great definition of it,” I complained.

“Of course, people discuss it in reference to Bloom’s Taxonomy, as ‘Higher Order Thinking Skills,’ but I think there is a simpler explanation. Critical thinking involves the students struggling to learn. If they don’t struggle, they aren’t really learning the information,” said Eugenia.

“My old dissertation chair used to say, ‘If you are comfortable, you aren’t learning.’ She always said you had to strive to be uncomfortable.” I added.

“Exactly,” said Eugenia. “Critical thinking is when there is struggle, but ‘struggle’ isn’t exactly the word. We need to find the exact word.”

I pulled up a thesaurus and started firing words at her, but she rejected them all. There was a silence as she thought. Then, she said, “Friction.”

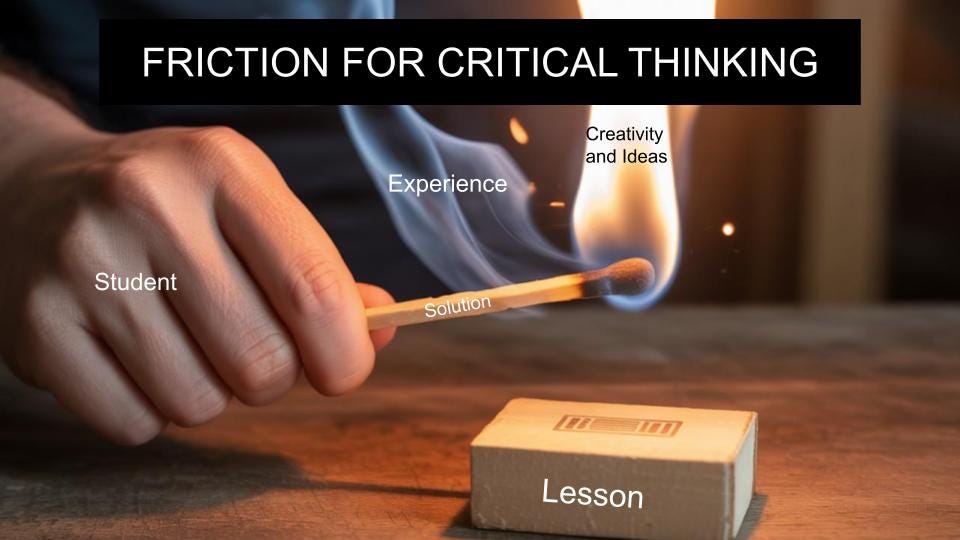

“I like it. I also like that friction makes heat, sparks, it sparks thinking and ideas . . .”

“. . . and creativity!” she added.

So we started talking about how friction is the essential component of critical thinking. When a task is easy to do, when it is simple to figure something out, or when we do something without thinking, it is because there is a lack of friction. We even have popular terms for this behavior—"skating" or “flying” through an activity—which infers that there is little or no friction when completing it. Friction is essential to pushing a student into critical thinking.

We already understood that on a visceral level, that problematizing an issue or introducing more difficult concepts promoted critical thinking, but the word “friction” clarified this discussion. The correct way to discuss what good teachers do in our lessons is “introducing friction.” We also know, instinctively, that a great way to identify a task that requires critical thinking is by gauging the amount of friction that must be overcome by a particular student to complete a particular task.

The concept of friction for critical thinking is not only a simple and elegant way to describe what is happening, it is also an excellent student-centered way to think about critical thinking. Friction is student-dependent. Some students, after they have reached a level of mastery at a particular task, experience much less friction in completing the task than students who have not achieved that level of mastery. For example, one student may find a quadratic equation daunting, requiring a high level of friction to complete. Another student may just plug in the numbers and find quadratic equations simple with little to no friction because they have done it successfully before. This is why good teachers, in general, are constantly adjusting their courses, striving to meet individual students’ needs to identify the appropriate level of friction. If we introduce too much friction, students give up; if we introduce too little friction, a student becomes bored and listless. This is why Eugenia went a bit further with the term:

“We need to call it “productive friction, not just friction. “Productive friction” is the right amount of friction to apply for critical thinking.”

How can you tell what level of friction is productive?

This is where formative assessment comes in, and why it is important to teach with low-stakes, scaffolded assignments that require frequent student feedback—especially now, as we learn to teach with AI. This is a brand-new pedagogical challenge that we must meet with the constant input of our students.

In our courses, we use in-action and after-action metacognitive reflection in our courses to gauge student understanding. This also helps our students to think about their own learning process, so it is a win-win strategy.

In-action metacognitive reflection involves having the students footnote their work to discuss their creative and analytical process as they completed an assignment. This is a technique that Eugenia brought to our collaboration, something she had been doing for years in her classes before AI was a thing. Reflective Footnotes can be used by an instructor teaching any subject. For example, a professor can require a physics student to footnote a particular the formulas they applied to their equations to explain why they chose that formula to solve a that particular problem, or a marketing student can footnote their application of a particular example to explain how it illustrates a concept they learned in class.

After-action metacognitive reflection involves writing a paragraph or a longer think-piece after the student has completed a task or project to discuss what they learned, how they feel about their learning process, and how they might apply the skills they have learned to a future task.

Both metacognitive activities are significant to what we do in our classrooms—providing important feedback to us while allowing student reflection on their learning process. We read those student metacognitive reflections frequently because they help us understand how the students are progressing, whether the activity was too difficult or too easy, and whether they actually benefitted from the lesson. Then, we immediately turn around and adjust the next lesson in the class, clarify directions, provide support, and sometimes increase the level of difficulty to meet our students at a specific learning level.

How Does Productive Friction Relate to Cheating?

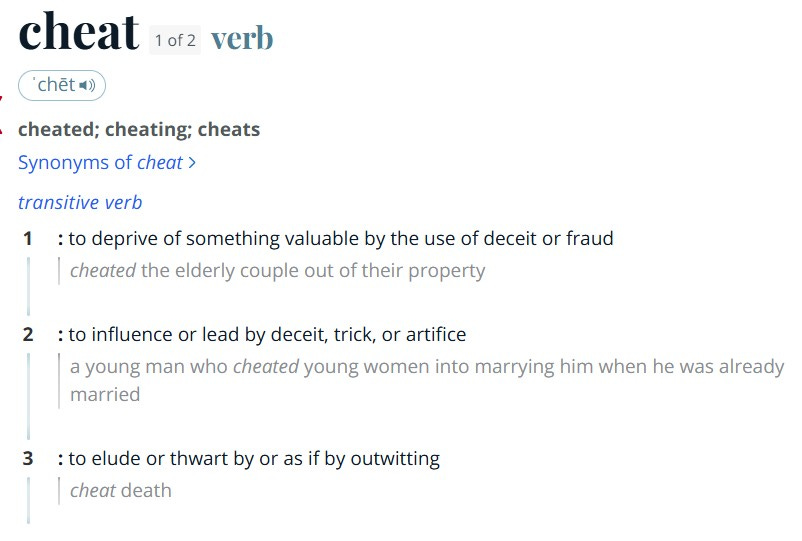

The significance of understanding how critical thinking is related to productive friction in learning is significant to defining “cheating”—especially in the Age of AI. Let’s start with a simple definition. Here’s how Merriam-Webster’s Online Dictionary defines “cheat”:

To be honest, that definition of cheating doesn’t really explain what we mean when we say our students are “cheating” in an academic capacity. I guess we could say that a student who cheats is depriving themselves of something valuable by the use of deceit or fraud, or that the student used deceit, tricks, and artifice to convince the instructor that the work they did was their own, or even that the student tried to outwit their instructor to elude or thwart their plans to teach the student something—but it all seems too ephemerally connected to what we mean when a student uses AI to write a paper for them and then turns it in as their own work. What, exactly, are we upset about when this happens?

You might say that you are upset that the student has squandered their opportunity to learn or that they have tried to take you as a fool (which we usually say in this circumstance), but even that doesn’t get to the heart of why we become so annoyed and infuriated by a student who cheats with AI. They have violated the rules, not just some academic code at your institution, but the ACTUAL rules of learning. They have ignored the system by which education exists—one of trust and companionable struggle where students work diligently under the tutelage of a dedicated educator toward understanding and the quest for knowledge. How does teaching with AI fit into this paradigm?

I admit that we struggled with this idea throughout our teaching. We were constantly questioning ourselves and what and how we were teaching every lesson. We wondered aloud (and quietly) how cheating differed from what we were encouraging our students to do every day in our classroom as they used AI to read, write, and research. We knew there was a significant difference between what we do and what was considered cheating, but we needed to clearly iterate what that difference was. We couldn’t let it remain unsaid, unprobed, and unchallenged. Not only did we need to make a clear differentiation between what we were doing and what was considered “cheating” for our own peace of mind, but we also needed to make that distinction clear to the students. If we didn’t fully understand the difference, we certainly couldn’t expect our students to understand it.

This is when our understanding of the role of friction in critical thinking became central to our understanding of cheating in the AI classroom. We redefined what we mean by cheating:

Cheating is the act of using AI to avoid friction.

This simple explanation helped us understand how our teaching and our students’ use of AI was not cheating. After all, we were using AI to INTRODUCE friction, and we expect our students to use AI to identify gaps, introduce opposition, and guide students toward understanding in a Socratic manner. On top of that, we expected our students to push back against AI, to argue with it, to reject the first answer, to fact-check, and to question any outputs. We constantly read our students’ interaction with AI in their shared chat logs, and we grade them on how well they complete the assignment and how much they pushed back against AI in their conversations.

We learned, from student feedback, that we were introducing the right amount of friction and that although students may not have appreciated how much work they had to do when interacting with AI, they were also grateful for the opportunity to learn deeply as they did so. Please see the post “Using AI in Writing Class: Student Voices” to hear what my students said about writing with AI.

The bottom line is this: If you want to teach with AI (and you should!), you will question yourself and your students all the time (and you should). To keep yourself centered and clearly define the difference between cheating and learning in your own work and in your students’ work, simply ask yourself: “Is AI being used to avoid friction?” If it is, it’s cheating.

It is important to be vigilant about how AI creeps into our lives and our work. We can’t let it make us lazy or uncritical. We have an obligation, to ourselves, and to our students to use AI in our teaching, and to teach our students where the line exists between learning and cheating.

"Cheating is the act of using AI to avoid friction." I really really like this definition of cheating. I have to let this sit with me for a bit to see if it feels thorough or apt for my own situation, but something I think about often is the reason why students cheat in the first place. Is it really to avoid critical thinking (internal friction), or to avoid critical punishment (external friction) that could bring about shame/social disconnection? Thank you for writing this; I'll be thinking about it for awhile.

As always a great write up! The definitions are simple yet profound!